The final recommendation of Senator Howard Baker's report into possible CIA involvement in the Watergate affair was that Michael Mastrovito of the Secret Service should be interviewed concerning his communications with the Agency on the day of the break-in. Mastrovito was never interviewed but in 2005, a year before he died, he responded to the “three insinuations” made in the Baker report above on his blog, which I stumbled upon recently.

On the day of the Watergate arrests, Mastrovito led the Protective Intelligence unit of the Secret Service in Miami Beach, preparing to protect dignitaries at the Democratic National Convention in July. “I had been there since late May in liaison with all police agencies, the FBI and the CIA," he writes. "The CIA chief and I met frequently.”

By “CIA chief,” he presumably means the Agency’s Miami station chief Jake Esterline. The paragraph in the Baker report refers to a phone conversation Mastrovito had with Esterline “later in the morning of June 17, 1972”:

"I had been advised by my Headquarters in Washington of the general details of the incident and that James McCord was one of those arrested. I knew little of McCord, had never met him, and did not know where he had been working. [Esterline] and I agreed that it was a stupid operation and we discussed McCord's involvement. The chief did not tell me at this time that others arrested also had CIA connections. Following our conversation [Esterline] sent a classified cable to his Headquarters reporting our conversation. I have never seen the cable, thus, I have no knowledge of what other comments he made regarding me. Obviously, [Baker's staff] took out of this cable only what they felt was pertinent for their interest and wrote the paragraph about me…To be the only name mentioned four times in one paragraph on the last page of this long report has been quite upsetting for me. If I had been called to testify, under oath or not, I would have responded to the three insinuations in this paragraph as follows…"

Mastrovito denies agreeing “to downplay McCord's Agency employment." He says he told Esterline “that the Secret Service convention advance group would make no comments regarding Watergate from Miami Beach” and “that it was well known that McCord had worked for the Agency.” He attributes this comment to Esterline “trying to impress his headquarters that he was attempting to keep the lid on McCord's previous employment.”

He also denies telling Esterline he was “being pressured for information by a Democratic State Chairman,” or any Democratic official. Convention Director Richard Murphy had been in touch with Mastrovito’s office and “was naturally upset that some of the Watergate perpetrators had come from Miami…[and] wanted assurances that the Secret Service would keep him updated.”

Mastrovito admits that Esterline did tell him “that the Agency was concerned with McCord's emotional stability prior to his retirement.” He writes: “My reaction was to laugh, knowing that this was his attempt to cover the Agency's backside. I also recall making a flippant comment to him on the order of ‘McCord must have been nuts to get involved in this mess.’"

Mastrovito never saw the cable Esterline sent to Headquarters summarising their phone conversation, so he didn’t know what else was said in the message: “Obviously, [Esterline] was under a lot of pressure, thus, his comments regarding our conversation were crafted to his advantage. I do find it shoddy tradecraft that he used my true name in a classified cable.”

Mastrovito felt Baker’s Minority Report “degrades the overall [Watergate Senate Committee] Report and will confuse historians in the future, plus, of course, give food for thought for the conspiracy theorists.” He regretted the fact that his name “will always be associated with this sordid affair due to the Star Chamber mentality of Senator Howard Baker and his staff. Shame on them.”

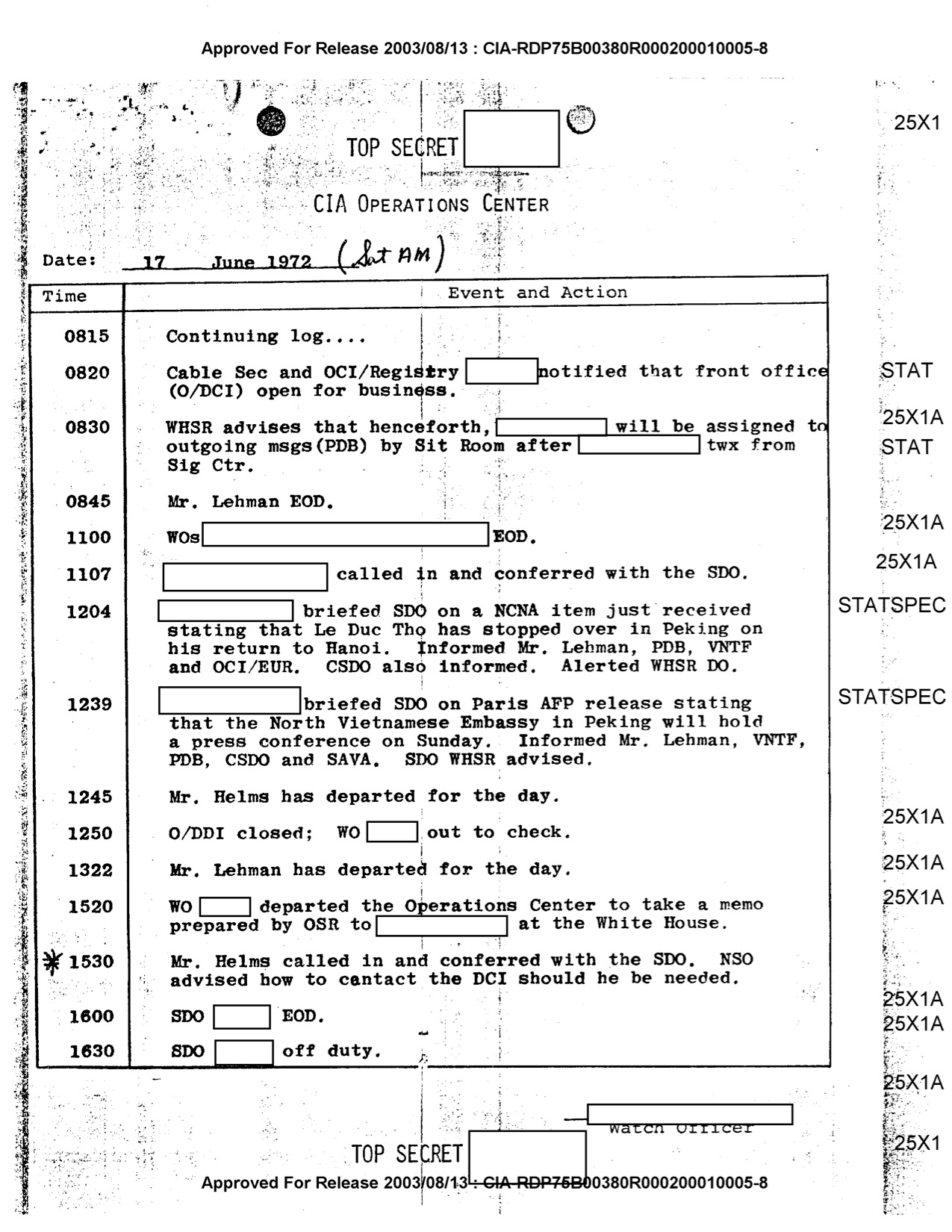

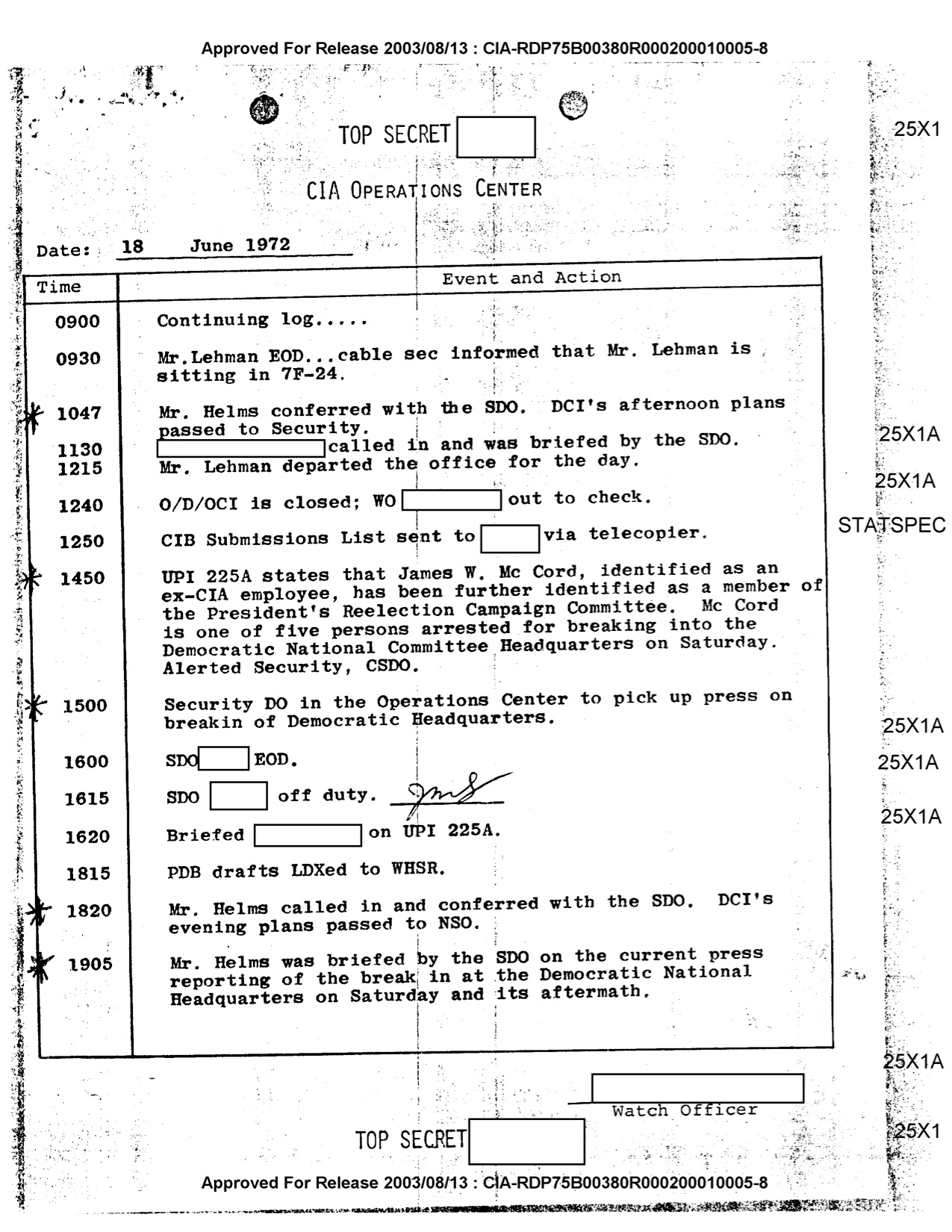

The timing of Mastrovito’s late-morning call to Esterline again raises questions about when CIA director Richard Helms first heard about the break-in. The CIA claims Helms was first alerted at ten o’clock that evening, as he prepared for bed, by Director of Security Howard Osborn. But a newly-discovered log from the CIA Operations Center shows Helms was at headquarters on Saturday morning and called in and conferred with the duty officer at three-thirty that afternoon.

CIA Operations Center log, 17 June 1972

CIA Operations Center log, 17 June 1972

CIA Operations Center log, 18 June 1972

Pat Boggs, the Deputy Director of the Secret Service, was the first to inform the White House of the break-in. Boggs called Nixon's head of security, Jack Caulfield, at “about 3 or 4 p.m.” on June 17 and told him Jim McCord, the head of security for the Nixon campaign, had been one of the men arrested. In the late afternoon, Boggs informed John Ehrlichman and told him a document referring to White House security consultant Howard Hunt had been found in the burglars’ hotel room.

But the CIA duty officer was still apparently in the dark. At 17:18, the FBI requested a search on "one Edward Martin...[who] claimed to have been employed by the Agency until several years ago." Martin was the operational alias used by McCord. At 18:30, when the Secret Service "requested namechecks on all those arrested at the Democratic Headquarters early this morning," the Office of Security could not identity Edward Martin as a former employee. Why had Esterline's cable still not filtered through to the duty officer or Security chief Howard Osborn and why were the Secret Service requesting a namecheck on Edward Martin when by now, they knew McCord and Hunt were involved?

Al Wong, the Deputy Assistant Director of the Secret Service, also played a key role in Watergate. Wong had recommended McCord to Caulfield for the position of head of security at the Nixon campaign. As Chief of the Technical Security Division at the White House, Wong also installed and oversaw the taping system which ultimately brought down Nixon.

On July 16, 1973, Alexander Butterfield revealed the existence of the Nixon tapes in testimony before the Senate Watergate Committee. Nixon wrote to the Secretary of the Treasury the same day, invoking executive privilege to block testimony from Wong (or any other agents of the Secret Service) the next day.

Within days of the Watergate arrests, a friend of Assistant Attorney General Henry Petersen who was "formerly with NSA" "advanced the theory that Wong directed 'this whole thing' using Ralph True who had some CIA connections." McCord met True on the afternoon before the break-in and later praised Wong as one of the heroes of Watergate.

25 years after Watergate, in an anniversary panel discussion on C-SPAN, Howard Baker still suspected there may have been a CIA or FBI component to Watergate, “an intelligence operation going on outside the White House in addition to the Plumbers.” “That’s been something that’s tantalised me for years," he said, "...[and] I’ll go to my grave wondering about that.”